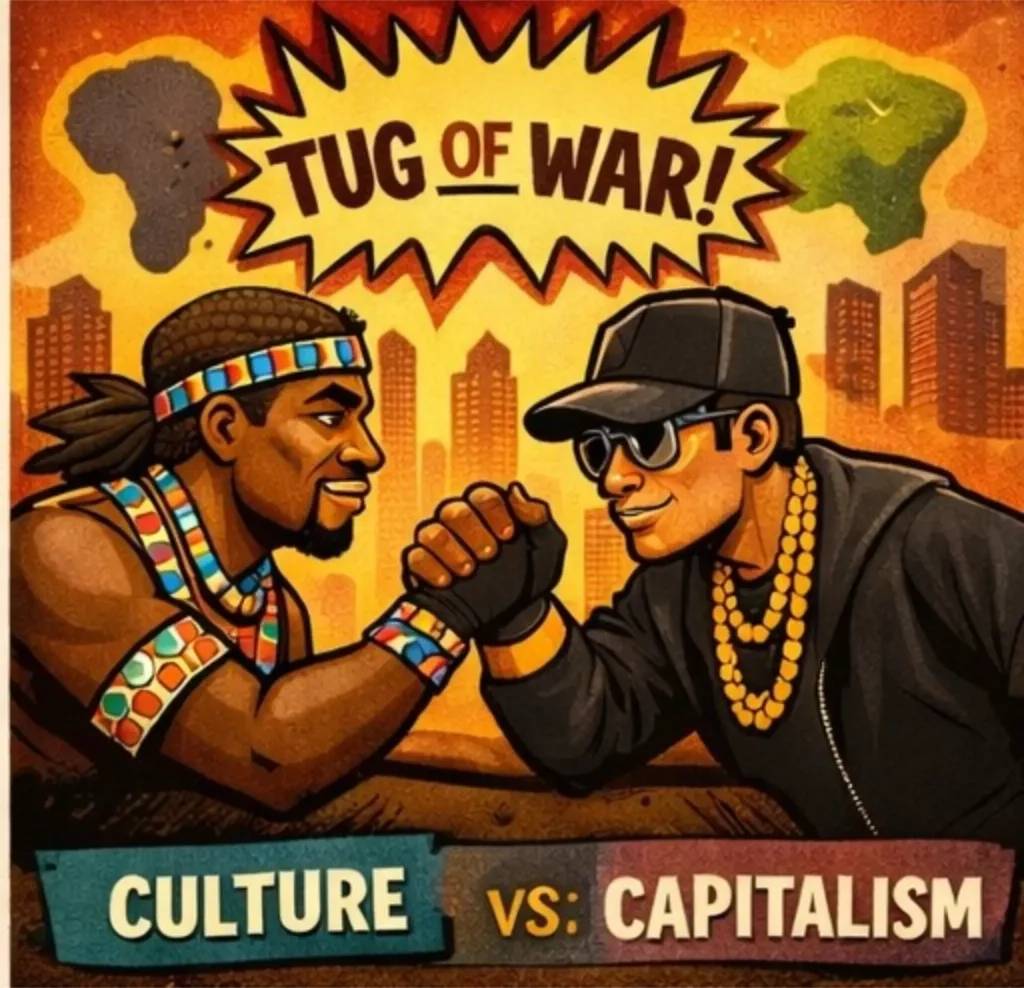

South African hip-hop has always existed as more than just music. It is a cultural language, a political diary, a fashion code, and a reflection of lived realities shaped by apartheid’s aftermath, township economies, migration, and youth resistance. Yet as the genre has grown in influence and profitability, it has increasingly found itself at the centre of a familiar tension: the pull between culture and capitalism.

This tension isn’t unique to South Africa, but here it carries a particular weight. Hip-hop arrived in the country as a tool of expression and survival, long before it became a viable business. Early pioneers used it to document street life, challenge power, and build identity in spaces where mainstream media offered little representation. From Black Noise and Prophets of Da City to Skwatta Kamp, Brasse Vannie Kaap, and Zubz, the foundation of South African hip-hop was unapologetically cultural before it was commercial.

As the industry professionalised in the 2010s, the relationship between hip-hop and money shifted dramatically. Major labels entered the space, brands followed, and artists began to see hip-hop as a pathway out of economic precarity. This was not inherently negative — in fact, it was necessary. For too long, hip-hop creatives were culturally rich but financially exploited. Capital promised sustainability, infrastructure, and global reach.

However, capitalism rarely arrives without conditions. The commercialisation of South African hip-hop has often demanded simplification. Complex stories are flattened into catchy hooks. Political nuance is replaced with lifestyle flexing. Language is adjusted for marketability. Sound is shaped by algorithms, radio formats, and brand expectations rather than community needs. In many cases, artists are rewarded not for authenticity but for proximity to trends that sell.

This has created a visible split within the culture. On one side are artists deeply invested in preserving hip-hop’s original purpose — storytelling, lyricism, social commentary, and regional identity. On the other are those who prioritise scalability, virality, and brand alignment. While these positions aren’t always mutually exclusive, the industry often frames them as such: you can be real, or you can be rich.

The truth, of course, is more complicated. Capitalism in South African hip-hop has enabled undeniable progress. Artists now own homes, fund independent labels, employ teams, and reinvest in their communities. Festivals, tours, and international collaborations are more common than ever. Hip-hop is no longer a fringe genre — it is central to youth culture and commercial entertainment.

But the cost of this progress is often cultural dilution. Brand partnerships increasingly dictate visibility. Playlist placements determine relevance. Metrics overshadow impact. In this environment, artists who refuse to compromise — those who rap in indigenous languages, resist trend cycles, or critique systems of power — are often marginalised, even as their work carries deep cultural value. Ironically, these same artists are later celebrated retrospectively as “legends” once their resistance is no longer threatening to profit margins.

Another layer to this tension lies in gatekeeping. Capital has created new power structures where access to funding, platforms, and media is controlled by a small ecosystem of decision-makers. This mirrors the very systems hip-hop once challenged. As a result, culture is sometimes repackaged and sold back to the community without the community having ownership or control.

Yet South African hip-hop continues to resist total commodification. Independent movements, regional scenes, and collectives have pushed back by prioritising ownership, storytelling, and long-term cultural impact. Artists from Limpopo, the Eastern Cape, the Cape Flats, and KwaZulu-Natal have shown that success does not have to look uniform. Projects rooted in language, place, and lived experience have proven that culture can still lead — even within a capitalist framework.

What’s emerging is not a rejection of capitalism, but a renegotiation of its role. The new generation of artists and curators are asking sharper questions: Who benefits from this deal? Who controls the narrative? What does sustainability look like beyond a cheque? There is a growing understanding that culture is an asset, not an obstacle. Without it, capital has nothing to monetise.

South African hip-hop is currently at a crossroads. It can continue chasing short-term profit at the expense of depth, or it can build models where culture and capital coexist without one erasing the other. This requires intentional choices from artists, media, brands, and audiences alike.

Culture is slow. Capital is impatient. Hip-hop lives in the tension between the two. And perhaps that tension — uncomfortable, unresolved, and constantly shifting- is exactly what keeps South African hip-hop alive.

![CTT Beats, Flash Ikumkani, Hannah V – UNDITHWELE [ Official Video]](https://dalakreative.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/126e2320-6774-67b8-c0d0-6e9f02af4d58.jpg)